Health Equity and Tobacco Use: UK TL1 Scholar Works Towards Effective Research, Treatment for People with Disabilities

LEXINGTON, Ky. (June 11, 2024) – When Sean Regnier started working with people with intellectual and development disabilities (IDD) ten years ago, he noticed a high rate of cigarette smoking among his clients.

“From a clinical standpoint, I was interested in figuring out how I could help my clients quit smoking,” he said.

Now a board certified and equipped with a master’s degree and PhD in applied behavior analysis, he’s working to develop smoking treatment options that are tailored for people with IDD. Regnier describes the current lack of such options as a serious health equity problem that leaves this population susceptible to long-term smoking and tobacco-related illnesses, especially since people with disabilities experience increased poverty rates and often lack of access to adequate healthcare.

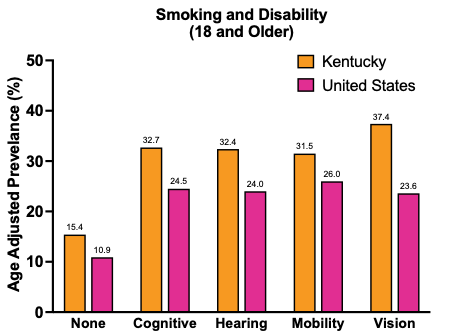

In Kentucky, the rate of smoking among people with disabilities is higher than the national average.

“We know that people with disabilities smoke at higher rates, even though they also try to quit at higher rates,” he said. “This suggests that people with disabilities are making strong attempts to quit, just like everyone else. However, they are running into important barriers that may prevent them from having success in treatment.”

Regnier points out that the health equity problem at hand is not simply a shortage of tailored treatment options—there’s also a dearth of research on smoking among people with IDD. He recently conducted a literature review that found only two published papers on the topic of smoking cessation treatment for this population in the U.S. In an effort to address this gap in knowledge, he’s now working as a post-doctoral fellow in UK’s Pharmacology of Addiction Lab (PAL), aiming to improve how smoking is assessed, measured, and treated among people with IDD.

Launching a Career

Regnier came to UK in 2021 to work with William Stoops, PhD, one of the principal investigators of the PAL, an international leader in addiction research, and the regulatory director for the UK Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS).

“Once I came here, I learned how many resources we have available to us at UK and it kind of blew my mind. I knew this was a great opportunity for me to dive into my research career,” he said.

“Working with Dr. Stoops and his lab have given me an unbelievable foundation for clinical research. I’ve gotten to learn all about pharmacology of drugs, how they work, how they affect the brain—all these things that are foundational to studying addiction. I’ve been able to run research sessions at our inpatient unit, testing potential medications for cocaine use disorder. And I’ve gotten to learn how research labs function—things like working with multiple principal investigators and managing the financial side of grants.”

Since coming to UK, Regnier has received a pilot grant from the department of behavioral science in the UK College of Medicine, an Early Career Investigator Award from the College on Problems of Drug Dependence (CPDD), and a travel award from CPDD as well.

His funding from CPDD supports his research on how to better measure smoking among people with IDD through adapting existing technology known as “smokerlyzers.” Meanwhile, the UK behavioral science pilot award funds Regnier’s research into improving assessment of why people with IDD smoke cigarettes.

“Modern cigarette smoking assessments have not been used with people with disabilities,” he said.

To begin addressing this gap in the research, he distributed a smoking assessment called FASTR (Functional Assessment for Smoking Treatment Recommendations) to adults with IDD who smoke cigarettes. He evaluated their understanding of the assessment and received their feedback on how it could be improved for people with IDD. The findings informed recommendations for practitioners on using the FASTR with people with IDD. A paper about this study has been accepted for publication in the journal Behavior Analysis in Practice.

In addition to the grant funding he’s received in his time at UK, Regnier was also selected for the CCTS’ TL1 Postdoctoral Training Program in Clinical and Translational Science.

“The TL1 program has been a wonderful experience for me and has helped me in so many ways. From the amount of exposure of I’ve gotten to the rest of my department through other mentors and trainees, to having funding for travel for conferences (they can get expensive!), my favorite part is the networking.”

UK’s Human Development Institute has been another instrumental collaborator in Regnier’s research since his early days in the Commonwealth.

“It’s a great back and forth collaboration,” he said. “I’m hoping to work with them for a long time.”

Beyond conducting collaborative research, Regnier and the HDI team work together at the Special Olympics Games to help inform athletes about the dangers of cigarette smoking and resources to help them quit. He also works with their women’s health group, which aims to inform people with disabilities about cancer and screenings.

On the Path to Independent Research

Building on the training he’s received and research he’s conducted with those supports, Regnier has now been awarded K99/R00 Pathway to Independence Award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The K99/R00 program is designed to accelerate the transition from a mentored postdoctoral research position to a stable, independent research position.

The grant will support his research to identify barriers and facilitators related to quitting smoking for people with IDD. Based on these findings he will adapt an existing smoking cessation intervention so that it’s tailored to the needs of this population. He will then evaluate its feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy.

“Some of the main smoking cessation treatments we currently have are rooted in behavior analysis. Contingency management, for example, was developed by behavior analysts,” he said.

However, current treatment options pose significant barriers for people with IDD, ranging from transportation to emphasis on extensive vocal-verbal behavior, which could be difficult for some people.

“The primary research goal with this grant is to develop a treatment that is accessible for people with disabilities—something that’s patient centered and flexible based on someone’s needs.”

Having received exceptional support from his mentorship team—including Stoops, Hilary Surratt and Hannah Knudsen of UK, as well as Jennifer Tidey of Brown University—one thing Regnier looks forward to in his future as an independent principal investigator is offering the same kind of mentorship to up and coming researchers.

“For me, a big goal is to mentor post-docs and grad students. I love being a mentor and watching other people develop.”

Advocating for More Inclusive Research

Regnier also hopes to push health research to become more inclusive of people with disabilities, whether through his participation at national conferences or his work at UK.

Due to his influence, the UK PAL is now incorporating the American Community Survey’s (ACS) six disability questions into their screening process for potential research participants.

“We screen hundreds of people a year at our lab, and we’re adding the survey to all our screenings—with the disclaimer that they won’t be excluded from the study based on their answers.”

He hopes to get more researchers to add these questions to their work to help address “the huge gap in data” about the health and health behaviors of people with disabilities.

Stoops agrees that disability hasn’t been considered in health research overall, but by incorporating the ACS disability questions into their lab’s universal screening process, they’ll be contributing to a better understanding of substance use and disability status.

“The NIH recognition of disabled people as underrepresented in research is a major sea change. We know a lot about addiction, about the brain, but we haven’t leveraged that knowledge for this community. The Americans with Disabilities Act isn't enough—we really need to work with people with disabilities and advocates to understand their needs. We’re at the beginning, and Sean is doing formative work.”

The project described was supported in part by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through grant number UL1TR001998. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.